Getting published

From draft manuscript to print,

Sue Burke reviews the process.

I made mistakesóand I persevered. Then disaster struck.

|

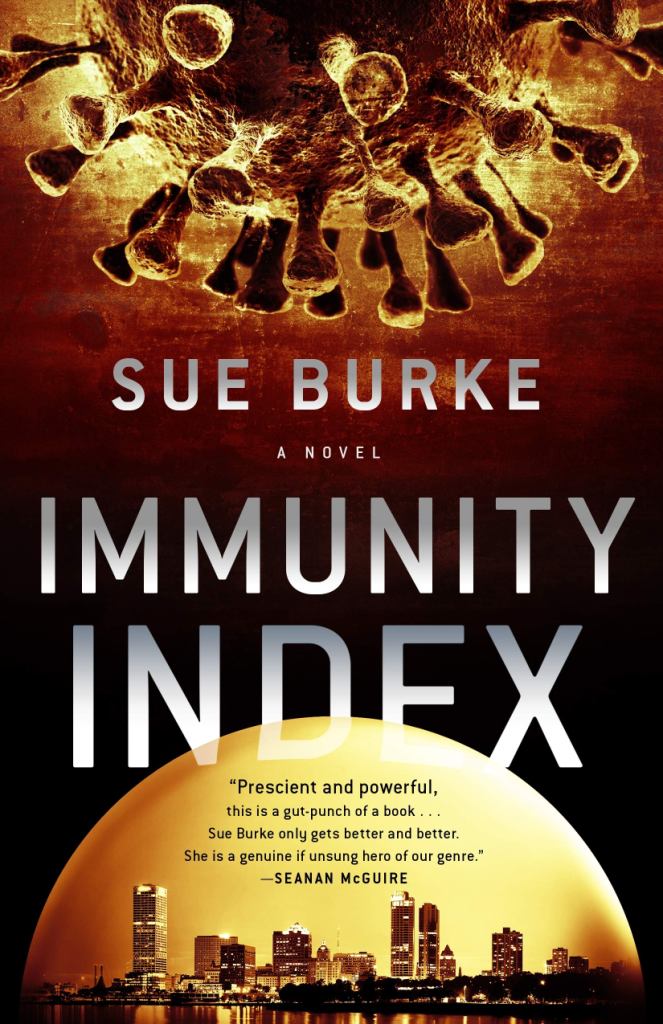

This is the story of the novel Immunity Index , which will be published on 4th May 2021. It isnít my first published novel. That one was Semiosis , published by Tor. Its hero is a talking plant on a distant planet, and it sold well enough that the publisher agreed to buy a sequel, Interference, together with another ďnovel-length work of science fiction.Ē

That contract demonstrated a lot of confidence in my ability as a writer. Because of the deal, I avoided the well-known agony of writing a pitch, summary, outline, or sample chapter, which I had done for Semiosis and Interference. I could do what I wanted, within the deadline.

Here comes the first mistake. I got to work on 20th March 2018, reviewing a folder of notes I have for ideas for stories, and I found one that I liked. Many writers have praised the creative freedom of pantsing (writing by the seat of one's pants or making it up as you go along) a work, so although Iíd previously worked with more or less complex outlines and plotting, I decided to give pantsing a go. It didnít work. The initial draft was limp and only half as long as it needed to be.

Chastened, I reviewed ideas for ways to improve and expand the failure. This time I made notes and, eventually, crafted a plan. I added another character, rearranged some chapters, and complicated the conflict.

That worked better. It also took a couple of more drafts, which I showed to beta readers, who helped a lot by suggesting further changes. A few more drafts later, as deadline was approaching, I showed it to my agent and editor, who thought it held promise, but... They shared some useful suggestions about ways to sharpen the conflict (the characters were okay) and offered much-appreciated patience as I started one more time from Chapter 1.

Then disaster struck. In early 2020, I was working on one of the final rewrites. When I began the novel, a coronavirus epidemic seemed like not an original idea but an interesting one, since sooner or later, some sort of epidemic was inevitable. Then reality crashed into inevitability, and I finished the ninth draft under CoVID-19 lockdown, feeling deeply troubled. Finally I realised what troubled me: my fictional epidemic was better than the ghastly real one, more emotionally satisfying and, best of all, much briefer.

I turned it the final, final, final manuscript on 13th May 2020. My publisher, Tor, runs an efficient ship, and the technical editing began. The copyeditor found important errors and was easy to work with, although we differed on the philosophy of hyphens. I let the copyeditorís judgement prevail.

Soon, I was shown the cover art, which I really have no control over, but the city skyline in the art did not correspond with the city in the book, Milwaukee, so it needed correction. The art also featured a looming coronavirus, which at first I disliked, but then I thought that because some people understandably want to avoid all things CoVID-19, it could serve as sort of a trigger warning.

As I write this, review copies are out, although due to problems with CoVID and printing factory capacity in the US, only electronic versions are available. An audiobook is being made, and I was given the chance to listen to the auditions for the voice actor. I suggested the more snarky one, and my advice was accepted; the story, while gritty, has lots of fun snark. Iím setting up launch parties (via Zoom), interviews, articles, and other publicity efforts in tandem with Torís campaign; this will easily amount to a hundred hours of work.

Pretty soon, Iíll get a box of freshly printed books. This used to be exciting: I could give them away to friends and family, donate them to charity, and pass them out at conventions. These days I see no one and go nowhere. A box of books of my last novel, Interference, still sits here in my home office, forlorn.

Reviews will start to come in soon (I hope), but Iíve learned to limit my attention to them. Positive reviews are helpful if they identify what I did well so I learn what my strengths are and what readers find evocative. This information may offer inspiration for future writing or a sequel, although I mean Immunity Index to be a stand-alone novel. Negative reviews either point out flaws that may or may not exist (readers can be inattentive), or they complain that the book didnít meet their expectations because they wanted an orange, and I delivered an apple; negative reviews are emotionally taxing and, worst of all, unhelpful.

Eventually, Iíll know if the book sells well. A book ďearns outĒ when the royalties for the author cover the ďadvanceĒ or partial prepayment of the royalties. Publishing finances can be complex, but earning out the advance is one bright line that authors do well to cross.

This brings me to the question bothering me the most. Will readers want to buy a book about a coronavirus epidemic? Existing novels about epidemics, such as Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and The Stand by Steven King, sold well during lockdown. As I said, my novel tells of a more exciting and in some ways better coronavirus pandemic than the one we actually have, and readers may appreciate an escape from our horrible reality into less horrible fiction. I just donít know.

I have decided that my next two novels will take place in the distant future, far from the reach of current events: I donít want to get outflanked by the present again.

Sue Burke

[Up: Article Index | Home Page: Science Fact & Fiction Concatenation | Recent Site Additions]

[Most recent Seasonal Science Fiction News]

[Convention Reviews Index | Top Science Fiction Films | Science Fiction Books]

[Science Fiction Non-Fiction & Popular Science Books]