Ghost stories from Asia

There are ghosts in Asia too

as Steven French finds out reviewing

Flame Tree Press' latest genre anthology

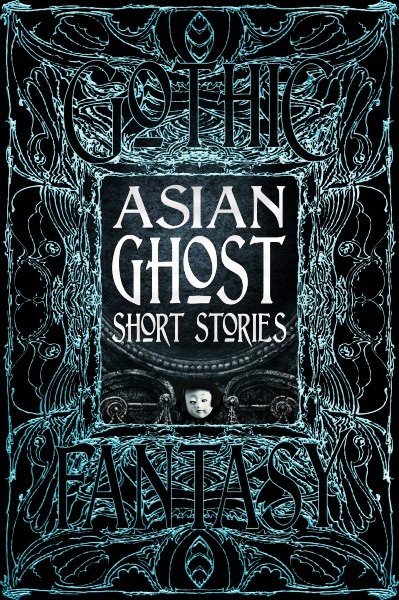

Asian Ghost Short Stories

(2022) Luo Hui & K. Hari Kumar (eds.), Flame Tree Press,

£20 / Can$40 / US$30, hrdbk, 430pp, ISBN 978-1-839-64882-3

|

|

|

This is definitely a book for dipping into rather than reading cover to cover! As with other collections by this publisher, the contents are organised by author’s surname, which means that, for example, there are no less than twenty-two pieces in a row by Pu Songling, described in the helpful and orienting introduction by Dr Luo Hui as China’s ‘Historian of the Strange’. These are drawn from oral traditions and written sources as well as personal experiences and range from the disturbing to the poignant, together with what amounts to straight-up reportage. So, in ‘The Cloth Merchant’, which is just a couple of paragraphs long, a cloth merchant comes across a run-down temple where a priest urges him to pay for repairs. After the merchant balks at the cost, the priest threatens to kill him at which point the merchant begs to be allowed to take his own life. A passing ‘Tartar-General’ then sees a woman in a red dress entering the temple. Upon finding no woman inside the General accosts the priest and breaks down a locked door, to discover the merchant hanging from a beam. Fortunately, he is not too late to save the man who, believing the woman in the red dress to be a divine manifestation, decides to repair the temple. The priest however fares less well and has his head cut off by the General.

|

|

Women, whether as ghosts or demons, feature prominently in many of these stories, often with Freudian overtones, as Dr Hui notes. In ‘The Painted Skin’, also recorded by Pu Songling, a man named Wang meets a pretty young girl along the road who asks him for his help. Taking her home he discovers that she is in fact a hideous demon, wearing the skin of a woman. Terrified, Wang asks a priest for help but the demon isn’t deterred and tears Wang’s heart out of his chest. Wang’s brother and the priest track the demon down and cut off its head, whereupon it becomes a column of smoke, which the priest captures in a gourd, rolling up the skin that was left behind like a scroll.

|

Pu Songling

Pu Songling |

|

At that point, Wang’s wife shows up and pleads with the priest to bring her husband back to life. Declaring that to be beyond his powers, the priest directs her to a local destitute man who berates and humiliates her and forces her to swallow a large pill, before disappearing. Tearful, the wife returns home to her husband’s body and while stitching up his wound, she feels a lump in her throat, from which pops out … a human heart! As it begins to throb, she closes it up in his chest and sure enough, by the next morning her husband is alive again, albeit sporting a large scar and ‘disturbed in mind as if awaking from a dream’.

A less weird and more poignant tale is offered in ‘The Fisherman and His Friend’, featuring Hsü, who likes a drink while he fishes by the river, always pouring a little wine on the ground as a libation to any drowned spirits. One evening a young man appears and accepts the cup of wine that Hsü offers. This cements a firm friendship, until the young man reveals that he is in fact the ghost of someone who drowned while tipsy and the next morning he is due to be reincarnated. However, he urges Hsü to return to the river the next day where he will find the ghost’s replacement. But instead of drowning, the woman concerned manages to save her baby as well as herself. The next evening the ghost reappears and confesses to Hsü that he could not bear to see the child left motherless and so saved her, at the cost of his return to the land of mortals. And so, their friendship continues, until the young man tells Hsü that because of his noble act, he has been appointed the guardian angel of a distant town. Hsü follows his friend there, and on arrival is feted by the villagers who have been told by their local deity to pay his travel expenses and give him presents, which allow Hsü to retire.

There’s a similar sequence of sixteen stories collected across Japan by Richard Gordon Smith. Interestingly, a number of these feature spirits associated with trees. So, in ‘The Spirit of the Willow Tree Saves Family Honour’, said spirit directs a down-at-heel nobleman to where a vast treasure is hidden. Likewise, in ‘The Dragon-Shaped Plum Tree’, the tree spirit intervenes to save an old gardener, at the expense of the tree itself. And in the atmospheric tale, ‘The Memorial Cherry Tree’, curio shop owner Kihachi is visited by a young girl, barefoot in the snow, trying to sell a painting of a beautiful woman. Kihachi buys it on the spot, thinking he has a bargain but after hanging it up, the portrait changes into a haggard and blood covered figure. Kihachi decides that he must return the picture to the girl’s dying father. However, when Kihachi hands it to the man, the latter not only tears it up and throws it into the fire, but jumps in himself, followed by his daughter. The story ends with an investigation that concludes that the painting was haunted by the spirit of a cherry tree and in commemoration a beautiful young cherry tree is planted in place of the old.

|

Lafcadio Hearn"

Lafcadio Hearn" |

Similar oddities can be found in the stories recounted by Lafcadio Hearn, who according to Hui, was a Greek-Irish writer who married a Japanese woman and collected ghost stories. Interestingly, his renditions are apparently considered the ‘gold standard’ in Japan but were translated into Japanese only after their publication in English. One of the creepiest is ‘The Reconciliation’, which tells the story of an impoverished samurai who divorces his wife and marries the daughter of a distinguished family in hopes of gaining advancement. However, this marriage brings him no happiness and his thoughts return to his first wife. Eventually his remorse is such that he decides to look for her at their old house. Upon returning he finds the rooms dark and empty, except for one that his wife favoured and where, indeed, she is sat, sewing by the light of a paper-lamp. Sitting down beside her, he tells her of how he has repented and asks her forgiveness. Which she gives and so they talk through the night, of the past and their new future together, until the samurai can stay awake no longer. In the morning, however, he finds that instead of a comfortable bed, he is laying on mouldering floorboards and when he turns to his wife, there is only a corpse, wrapped in the grave-sheet, and consisting of little more than old bones and a mass of black, tangled hair. (As Hui also notes, there is a line that can be drawn from this image to that of the figure from The Ring.)

|

|

|

Hair and a dead body also feature in ‘The Corpse-Rider’ where to escape the vengeance of his divorced wife, now dead, a man must ride her corpse through the night, clutching her hair as reins. Even creepier is the story, ‘Ingwa-Banashi’ in which a lord’s dying wife asks one of his concubines to carry her into the garden to see the cherry-tree in blossom. But as she climbs onto the concubine’s back, the dying woman slips her hands under the girl’s robe and, clutching her breasts, cries out that now she has her wish for ‘cherry-blossom’, before promptly dying. The poor girl discovers that the dead hands have merged with her flesh and cannot be removed. The only recourse is to cut them from the corpse, but as if it wasn’t horrible enough to have a dead woman’s hands affixed to her body, the concubine discovers that they continue to have a kind of life of their own, squeezing and compressing her breasts every night at the Hour of the Ox. Even after becoming a mendicant-nun and performing good works for years, the concubine cannot exhaust the evil karma and after telling her tale at a rest-house, ‘nothing more was heard of her.’

A similar combination of dead-pan re-telling and creepiness can be found in the eight tales from S. Mukarji. So, in ‘His Dead Wife’s Photograph’, a clerk asks a photographer to take a picture of his wife and sister-in-law. Upon developing the photo, the image of a third woman is seen who turns out to be the clerk’s first wife. She too was keen to have her picture taken but immediately after dressing up for the shot, the couple have to dash off to attend to her sick mother. Shortly after returning the wife dies and the ‘scientific’ explanation is that somehow her image was projected onto space such that years later, it returned just as the new photograph was being taken.

A dead wife also features in ‘What Uncle Saw’, with the ghost returning to her husband two nights a week but apparently acting benignly. In ‘What the Professor Saw’, however, it is a brother who appears one morning to urge the Professor to take care of their mother after he is gone. And, of course, the brother had died hours earlier.

As these stories indicate, not all ghosts are malignant and some that are, are easily tricked. So, in one of the stories that Lal Behari Dey collected, called ‘The Ghost Who Was Afraid of Being Bagged’, a ghost threatens a barber who uses his shaving mirror to convince the ghost that he has another in his bag. Terrified of being ‘bagged’ the ghost agrees to bring the barber gold and fill a granary with paddy. The ghost’s uncle, seeing his nephew put to work like this, resolves to challenge the barber himself but likewise is fooled by the mirror and agrees to fill another granary with rice.

At the opposite pole to such stories is the ‘The Phantom Rickshaw’ by Rudyard Kipling. As Hui notes, eyebrows might be raised at the inclusion of the likes of Kipling in such a collection, but in this tale the ‘colonial gaze’ is inverted as the position of supposed superiority becomes destabilised through an encounter with ‘the Other’ (p. 19). Here a British man has an affair with the wife of an officer on the journey over, only to abandon her. The woman dies but her ghost repeatedly reappears, in front of the Club and at the Mall, carried in her yellow-panelled rickshaw, beseeching her former lover to return to her and eventually driving him to a complete breakdown. The story nicely entwines the triple oppressive elements of the local environment, British rule (perhaps inadvertently) and a dreadful haunting, ending with the narrator’s terror at his impending death, coupled with, belatedly, feelings of remorse.

|

|

Also writing ‘under the shadow of British colonialism’, as Hui puts it (p.18), was Rabindranath Tagore, another literary giant. ‘The Hungry Stones’ presents a story within a story, as travellers waiting for their train connection are regaled with a tale about a haunting by a solitary and abandoned house – or rather, a former palace, now occupied by a newly-appointed collector of cotton duties. Dismissing the warnings not to stay the night, the man finds himself entranced, initially by the laughter of young women and the tinkle of anklets, until his nights in the palace, among the ghosts, come to seem more real than his days at work. The spell is broken by the cries of a local madman, shouting ‘All is false!!’ and the narrator learns that the stones of the palace have soaked up all the ‘countless unrequited passions and unsatisfied longings and lurid flames of wild blazing pleasure’ (p. 391) that have raged within, so that no one can now escape their ‘cruel jaws’, at least not without losing their reason, except by one means. What that is, we are never told for then the next train arrives and Tagore leaves us in suspension.

|

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore |

|

|

Another of his pieces - ‘The Lost Jewels’ - likewise begins with the narrator pulling up in his boat next to an old bathing ghat, and encountering an old man who tells him the tale of Bhusan Saha who married a beautiful woman. Unfortunately, Bhusan’s business ran into difficulties and he had to travel to Calcutta to raise funds. While he was away, his wife, fearing that she would have to sell her jewels, ran away with her cousin. After returning home Bhusan searched all over but eventually gave up hope of ever seeing his beloved wife again. Then one dark and stormy night he heard the jingling sound of ornaments, coming up the steps of the ghat. In terror he saw, by the light of the moon, a skeleton festooned with previous jewels. Following it back down the steps, he suddenly woke up as his feet touched the waters of the river and fell headlong to his death. “Do you believe this story?” the old man asks. “No, ” the narrator replies, “for I am Bhusan Saha.”

The details here are beautifully laid out and the gothic atmosphere nicely developed. What leaves an unpleasant taste is the explicitly misogynistic message it contains, that ‘excessive devotion’ will spoil a woman and cause her love to atrophy.

Scattered between the old tales are a number of commissioned stories which may be more to a modern reader’s taste. In ‘Purple Wildflowers’ by Alda Yuan, set in the American West, a young medium, herself possessed but able, as a result, to speak to the spirits and encourage them to move on, is called upon to deal with a case of multiple possessions at a mining depot. Bookended by her interactions with a couple of guys who give her a ride in their carriage, the story nicely captures the immigrants’ sense of dislocation and longing for home, while ending on a suggestively positive note.

Nur Nasreen Ibrahim’s ‘Picture of a Dying World’ likewise conveys that feeling of dislocation, mixed with loss of familial connection, as the narrator returns to their home village after their mother’s death. Here ghostly visitations are mixed with painful memories against a backdrop of looming ecological disaster.

In K. P. Kulski’s ‘The Pavilion of Far-Reaching Fragrance’, the events in an ancestral home echo down through the decades, as the betrayal by a Queen’s guard curses his descendants. The story oscillates effectively between the horrific assassination of the monarch in late-nineteenth century Korea and the present day, as the US-born narrator inherits the ‘gwishin’ on her mother’s death. The final paragraphs, as the ghost climbs up her body, to wrap its peeling arms around her, in a ‘loving embrace’, grinning with its ‘terrible mouth of blood’, are truly creepy. The tale ends with a warning: you’d better hope you find no horrible misdeeds committed by your ancestors in your family’s stories, lest you look in the mirror and see a ghost, sitting on your shoulders!

In a review such as this, I can mention only a few of the stories contained in this anthology but I hope I have given some sense of their diversity, not only when it comes to the cultural context but also in terms of content and tone.

Asian Ghost Short Stories is not a complete anthology of ghostly horror from that part of the world, nor is it representative. However, it does provide a useful window onto ghost-genre stories that may be unfamiliar to many readers.

Dip in and be chilled!

Steven French

[Up: Article Index | Home Page: Science Fact & Fiction Concatenation | Recent Site Additions]

[Most recent Seasonal Science Fiction News]

[Convention Reviews Index | Top Science Fiction Films | Science Fiction Books]

[Science Fiction Non-Fiction & Popular Science Books]

[Posted: 22.9.15 | Contact | Copyright | Privacy]

|

|