A Worldcon future

Worldcons in Europe have been under pressure.

Now, not least because of SARS-CoV-2, things may change,

muses Jonathan Cowie. As the science symposia organising

community have been finding out, there are interesting options.

My Worldcon relationship

One problem

Solutions

Environmental sustainability

Possible ways forward

References

My Worldcon relationship

Before beginning, I have to confess to having a love-hate relationship with Worldcons. I do kind of love them, but they are not a regular fixture in my diary. Yet, over the decades I seem to have inadvertently racked up a few: Brighton (twice), Great Britain; Glasgow (twice) again Great Britain; The Hague, Netherlands; Toronto, Canada; Melbourne, Australia; and London, once more Great Britain.

I greatly enjoyed my first, Brighton in 1979, organised by the Hugo rocket builder Peter Weston. I was younger then and could take days of heavy programming, and nights of even heavier partying, in my stride with nary worry. I went with around a score of fellow students from three Brit colleges (Hatfield, Keele and Warwick) that then represented about half of British Eastercon student fandom of the time. The intense programming and transatlantic attendance, with authors walking about who previously were just names on treasured book covers, was simply wonderful. And it was big, simply HUGE: there was a smidgen over 3,000 attending! OK, this seems small beer when today a European or US Worldcon can see getting on for 10,000 attending. But the 1979 Worldcon was, for its time, huge. Remember, the previous year's, London-venued, hence for its time large, Eastercon (Britain's national convention) saw a paltry 600 of us gather. So something five times the size was, in British fandom at the end of the 1970s, genuinely special.

Today, I am longer in tooth, have less stamina and, of course, with each successive Worldcon getting further (new) 'added value' out of them has, by definition, become harder.

And then there's my conscience. If I travel abroad – for the said added value – there's the fossil carbon burden. Justifying Melbourne (2010) was hard. Increasing the benefits to offset the fossil carbon costs necessitated: combining the trip with another nation's (New Zealand's) SF natcon, two NZ science business meetings, two NZ science site visits, and two Australian science business meetings (not to mention – don't tell anyone – one arts symposium reception). The trip's fossil carbon returned my annual carbon budget (previously of half the average UK citizen's) to the national average: it doubled my personal fossil carbon burden for the year. Given that air miles globally have grown markedly the first two decades of the 21st century (well, at any rate, up to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic), it is an increasing factor driving ever more increasing global greenhouse emissions. Prior to 2000 AD emissions from aviation accounted for around 1% of greenhouse gas emissions, today (2020) it is around 3%. We are all individually going to have to start thinking about the environmental impact of travelling to international events.

For example, a return flight from London to San Francisco will incur a passenger fossil carbon burden of 4.4 tonnes of carbon dioxide. So these days, most years I simply will not fly let alone do long-haul. As an environmental scientist, and vaguely responsible citizen, I patently can't justify it, and certainly not defend it on a regular basis. Flying for me is now rare and I expect I will now only make one or two long-haul return trips in my remaining lifetime. (Fortunately, in terms of fecundity, my heritage fossil burden for future generations is zero.) For all the talk of diversity and such, Worldcon regulars might wish to remember that they are part of the global elite: their income is likely to be in the top 10% of the global population's! Further, within elites there are elites: for example, here in the UK, 15% of our population undertakes 70% of the flights.

Finally, there are my personal tastes that affect my decision to attend a Worldcon. In addition to meeting old friends and acquaintances as well as encountering authors, two of my favourite convention aspects are the science and film programme streams. (Others will have their own individual likes.) For me, a Worldcon that has an international range of independent films provides a rare opportunity to see the best cinematic SF has to offer across the world (well done Melbourne 2010!). Also, a Worldcon that has a broad, multi and interdisciplinary science programme is greatly preferred (well done Toronto 2003) over one that is minimal or, as bad, focusing on just one discipline (often space related science) with the rest of science squeezed into half or less of the science programme stream (and worse the rest of science being poorly scheduled and venued).

Fortunately, there's a lot going on at Worldcons. Typically, with well over a dozen parallel programme streams, there's something to tempt even the most specialist and/or eclectic attendee. And then there the big events – such as the masquerade and Hugo Awards – that attract many. So each year the average discerning SF fan has to weigh up their personal pros and cons in deciding whether or not to go.

One problem

Yet one problem, certainly with European-venued Worldcons, in recent years has been overcrowding. This is not entirely Worldcon organisers' fault, Western Europe simply does not have a decent single conference venue with sufficiently large halls for the main events (such as the Hugo Award) as well as a score of smaller halls with each seating between at least 200 and 400 people that are needed for the specialist programme streams. So, given lacking facilities of the sufficient size for a large European Worldcon, it really is important from the outset for the convention's organisers to plan (and budget) for a size of attendance that the venue can properly cater, and not anything larger. Now, it should be possible to restrict numbers to the size of the venue and budget accordingly but, for whatever reason, recent European Worldcon committees have been either unable or unwilling to demographically plan. This has resulted in recent European Worldcons having long queues for specialist programme items (what's known in large science conferences as breakout programme items) with many (repeat 'many') attendees being turned away. It was bad enough for London (2014), worse for Helsinki (2017) and, even after both those, the Dublin (2019) Worldcon organisers still failed to get a grip. It's no joke. Further, problems with an overcrowded Worldcon manifest themselves beyond the convention: they put pressure on local accommodation as well as eating and drinking places. But fundamentally, future conrunners might want to check their moral compass in putting on an event that will see many not be able to attend the programme items for which they paid a four-figure sum in registration, travel and accommodation.

Fortunately, if one personally knows of the organisers, irrespective of their standing/popularity in fandom, one can ascertain their organising experience/competence in advance to the event. Failing that, it is possible to look up a proposed Worldcon's venue (they all have their own websites to tempt conference organisers), to ascertain how many seats its specialist programme areas can handle and then find out how big a Worldcon is being planned. If the proposed convention size easily fits the venue then great. If not, well an overcrowded event will not become my problem: I simply wont go. (I successfully dodged Helsinki and Dublin.) Sadly, such pre-convention reconnoitring is a necessity unless, of course, one does not mind the risk of attending what might be a bit of a bun fight. (As said, I'm not as young as once was and, having had a number of Worldcons under my belt, there is no longer any novelty factor. Conversely others may enjoy overcrowded events. Good for them: I respect diversity of opinion.)

Finally, Worldcons have to compete with the plethora of other major conventions in the con diary and, for myself, SF publisher events. I'm nearly an hour away by train from London which is where all the major UK publishing houses SF/F imprints are based. So it is easy to pop down to a publisher bash or book launch. These are less crowded affairs than Worldcons with a high author-to-participant ratio. As SF² Concatenation usually gets a press invite, these are a low-cost, high-return way for me to meet both SF authors and publishers.

Pulling all these together means that these days a Worldcon has really got to prove that they are competently organised if they are to even begin to tempt me as a physical participant. Indeed, the past year when discussing with fan friends the possibility of this article, I discovered that I was far from alone: a number of convention regulars are becoming decidedly choosey as to which cons to attend and that includes Worldcon when they are held in our country or continent.

Future European Worldcon organisers really do need to address this issue. A fourth European Worldcon in a row of increasing overcrowding would not be something of which to be proud.

Solutions

Fortunately there are solutions. First up, YouTubing Worldcon programme talks is a real boon (YouTubing panels are of less value as typically there is less preparation and panellists tend to shoot the breeze and from the hip). YouTube videos mean that even if a registrant is unable to attend an item then they can catch it later online. Further, if Worldcon attendees are aware in advance that a programme item will be archived on YouTube then, if they are not a die-hard enthusiast of the topic or person, they may skip physically attending in the first place knowing they can catch it later online and so reduce queues of others for that item. Win, win.

Some conventions have been experimenting with YouTube. These include the 2016 Eurocon in Barcelona (links to some of their programme vids here) and the 2017 Worldcon in Helsinki (links to some of the programme vids within coverage here). If welcome moves like this continue then it would be an idea to have them on dedicated YouTube channels for all Worldcons (and Eurocons) managed by, say, WSFS (or respectively ESFS) under whose auspices the conventions are run. This would also provide a readily locatable visual archive of the conventions and so also provide heritage value.

This is all well and good, and as said I had been meaning to pen the above for an article for some months when SARS-CoV-2 spread, and everything changed. 2020 has seen a number of SF events experiment with placing more material online and becoming virtual.

Many conventions cancelled but some decided to go online as virtual gatherings and for them this has been something of an experiment. This is less so in the world of science and symposia organisation.

As with SF conventions, science symposia come in all shapes and sizes from small specialist one-day events through to full-blown, multi-programme streamed, international conferences spanning four or five days. Yet, in recent years there have been concerns, especially by science disciplines whose work touches upon environmental sustainability. Envrionmental sustainability related expertese is found in quite a range of subjects from biological conservation, through the environmental and geological sciences to Earth system science and Earth observation, with various specialisms drawn in along the way, such as computer science for modelling.

Environmental sustainability

A few years ago (2015), a Nature editorial summed up the environmental sustainability concerns of science symposia and events: the science equivalents of SF cons.

"Every time the United Nations climate negotiations get underway, media stories appear about the carbon emissions generated as thousands of government officials, environmentalists and scientists fly in from around the world. Similar questions have been raised about major environmental-science conferences, such as the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), which last year drew an astounding 24,000 people."(1)

So, thought is being brought to bear on the matter.

Where we are today is that major, physical conferences are far from dead: other than personal meetings, serendipitous encounters as well as networking do not work well on line. Having said that, scientists are finding that one does not have to attend every single major annual international conference in their discipline especially if there are online alternatives to mitigate the loss of some of the benefits of physically attending. Even so, some science conferences are only held online, such as Virtual Island Summit. But last year's AGU (2019) was as big as ever with 28,000 attending; that's roughly three times the size of a current larger Worldcon.

The journal Nature recently (2020) published an article on an analysis of that event's fossil carbon burden.(2) It had been calculated that the 2019 AGU's 28,000 delegates travelled 177 million miles (285 million kilometres) to get there and back – that's almost twice the distance to the Sun. In doing this they emitted about 80,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide: that works out at about 3 tonnes per scientist. Also, 75% of the AGU's greenhouse emissions were generated by intercontinental flights.

Now, other than the AGU being roughly three times the size of a larger Worldcon, they are similar in other ways to a North American venued Worldcon. The largest number of delegates came to the 2019 AGU from North America with the next largest visiting nationalities collectively being European. Like the Worldcon only a few come from Australasia and even less from Africa. The only difference from the Worldcon is that, for the AGU, Indian and Asian participants are a little more common. Broadly though, there are mostly similarities.

Looking forward, there has been discussion as to how the conference might look in the future.

One option is to put all the conference sessions and panels online and go virtual. This is what the European Geosciences Union (EGU) did in May 2020 in the middle of global CoVID-19 lockdown. The EGU normally sees some 16,000 attend, this year's (2020) virtual conference saw 26,000: that’s an increase in participation of nearly two thirds!

Another alternative would be to have a combination of the two: a physical Worldcon with a virtual one tagged on. Virtual registrants would get the con publications and voting rights with a registration fee pitched somewhere between supporting and attending rates.

Yet another possibility has been mooted by those who did the AGU analysis and that is to have not only a mix of physical and virtual but to have two or three physical hub events simultaneously elsewhere across the globe. These would be linked to the principal event by dedicated virtual-room facilities. The sustainability advantage would be that participants need only travel to the event closest to them.

There is, though, one problem with linked, simultaneous events on different continents: the time differential between the principal event and the hubs might mean that while much of the programming took place between 9am and 5pm local, principal hub time, the hubs at other longitudes would have to adjust. One way around this would be to have some items at the principal event take place in the evening. Those looking at future AGU options are considering for one year having San Francisco as a principal venue with a hub in Tokyo and another in western Europe. Could such a hubbed Worldcon work for the SF community? Either a British venued Worldcon or a North American east coast Worldcon could link up with the other as a hub as the time differential would only be five hours. As 9am to 5pm on the east coast US corresponds with 2pm to 10pm in Britain, and conversely, 9am to 5pm in Britain corresponds to 4am to midday in the North American east coast, North America being the site of the principal event would probably be more workable. Compensating, western Europe might combine their hub event with that year's Eurocon.

There are though a few workarounds to some of the afore hassles. Some programme items might be held outside the 9-to-5 window, while others might be recorded and then relayed just a few hours later to the hub events. While everyone might not marry up exactly in real time, only a talk's speaker might wait a few hours until after the hub event attendees have seen the recorded version of their talk and at that point join in online to answer questions from distant hub participants. Science symposia are beginning to find out that a big 'no no' is asking speakers to give talks after midnight: speakers should only give presentations after 10am and before 8pm; recorded versions should be used outside those windows.

Talking of venues, the international science symposia and events scene is now beginning to discuss how venue nations are chosen. As with Worldcons, a good proportion of international science symposia have codes of conduct and conduct reporting mechanisms. These support equity, diversity and inclusion around gender and orientation. Yet some nations that regularly host international events have a culture and even legislation that not only discriminates but even outlaw certain orientations.(3)

A small survey of 30 international ecology and conservation symposia between 2009 and early 2020 revealled that about half had codes of conduct. Yet nearly 40% of the conferences were held in countries where societal norms and laws discriminate against orientation and/or gender. Indeed, here only two provided information on their web pages as to how they planned for participants general safety such as in transit between accommodation and venues.(4)

In one sense this is not a new problem but environment and circumstances have changed. Prior to 1990 within SF fandom, or at least those fans operating at the international European level, there was a quasi-policy to try to hold Eurocons alternately in western and eastern Europe. Even following the fall of the 'iron curtain' in 1990, this has continued though today many Eastern European countries are far more liberal and progressive. Back then, pre-1990, the need to forge bridges between eastern and western Europe trumped diversity, orientation and inclusivity issues.

Today diversity, orientation and inclusivity is more of a concern. Also, today a number of the nations that are less liberal are also failing to adhere to international treaties regarding human rights, borders and international waters, let alone with other specific nations.

The question therefore arises as to whether Worldcons should be seen to be participating with such nations especially as such events can only take place with the active permission of its ruling political class?

Again, a solution is for international events to be held in liberal countries near those that are not, so that scientists and/or SF fans from those latter nations can attend with less distance to travel. This too can lower the event's fossil carbon burden especially if the physical event has a solid online dimension so reducing numbers from far away attending.

Of course, one has to be aware of the environmental cost of virtual events and virtual add-ons to physical gatherings: they are not zero fossil carbon options! In recent years some conventions have claimed that using packages such as Grenadine and online programme scheduling is more environmentally friendly than having paper programme sheets. Actually, it depends. If the programme is properly organised in the first place and it is clear in advance that no timetable changes will be made (even if some items are cancelled on the day), and if the paper is recycled with the original use from local sustainable forestry, then the paper option is actually quite environmentally friendly.

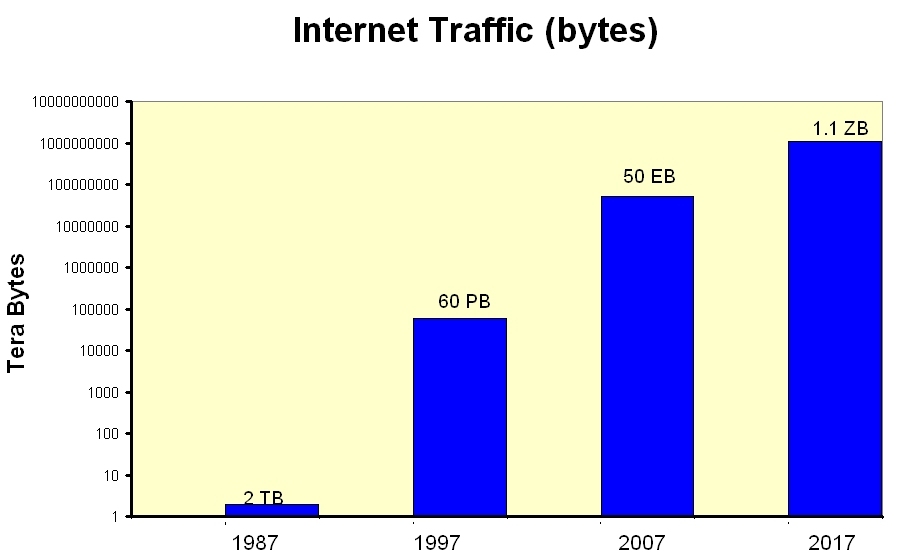

Surprised? Well, don't be. While virtual and/or part-virtual events save much fossil carbon from long-distance travel, they are not without environmental cost. Networks, information and communications technology, data centres, as well as peripherals (smartphones and PCs) all consume electricity as, indeed, does the manufacture of the technology (and that's not including all the rare Earth metals involved). The electricity involved in the manufacture of networks tech and peripheral device use has remained broadly constant the first two decades of the 21st century: efficiency gains have offset growth in use. What has increased – and increased markedly – is internet traffic and the amount of data held in data centres: these have grown near exponentially and they take energy to maintain and transmit. In 1987 global internet traffic amounted to 2 Terabytes but by 2017 it had grown to 1.1 zetabytes. Indeed, plot this in a chart (see below) and the traffic for the years 1987 and 1997 are so small that they cannot be seen (even though the figure for 1997 was 60 petabytes).(5) Consequently, the graph below of internet traffic has a logarithmic scale: so the y axis is not 1,2,3... but 1, 10, 100...

Note, a zetabyte is a billion, times more than a terabyte. As for a terabyte, a terabyte is 1012 bytes. If you bought a reasonable home personal computer the past three or four years, then its total disc memory could well be between 0.5 and 2 terabytes.

Annual internet traffic (bytes) in 1987, 1997, 2007 and 2017.

By 2018 it took 1% (200 terawatt hours) of global electricity generation to run data centres; you might want to think about that the next time you see someone taking a picture of their dinner. Add in information and communications technology, consumer devices (computers, televisions and smart phones), networks (wireless and wired) manufacture and use, and the internet and its technology account for around 10% of current global electricity production! Some forecasts have it that this figure could exceed 20% of the current, 2020, level of production by 2030 (though, of course, electricity generation itself will have by then grown a bit by then).

All this would not matter if the electricity was generated by non-fossil nuclear or renewables, but today most electricity is still fossil fuel generated: globally in 2018 it was 64%, also 64% in the US, and still 46% in the UK.(6)

Possible ways forward

What this all means is that if the SF community really wishes to make conventions more environmentally friendly/sustainable as well as accessible to a larger number of participants, then it needs to do a number of things. Yes, increase remote access and online archiving of programme items, but not to archive everything: much of the ancillary social media controlled by the event should be deleted at the event's end (which should be done anyway for privacy reasons). The other thing is to get events' management properly balanced between electronic and paper.

Now, at this point some convention organisers (conrunners) may be bewailing that this is all too much and that it will never happen. Well, think again. Post SARS-CoV-2 / CoVID-19, the world is changing. We now realise that for many working from home is perfectly doable and as productive an option so enabling fewer trips to the office. Indeed, we now think differently about what 'essential travel' really means. Also, we know that teleconferencing and virtual meetings are routinely possible: it never took off as it did with CoVID-19 lockdown. Yes, virtual events may not be as good as the physical, real deal, but then the argument is to decrease the frequency of real event physical attendance (not eliminate it) and greatly boost virtual and real-virtual event participation. Certainly if the experience of the EGU is anything to go by, then there will be a substantive increase with virtual participation that will bring in more revenue than is needed to run the technology and provide physical paper documentation (programme schedule, souvenir booklet and so forth) to this new group of participants.

Some conrunners might bewail that the technology is not good and reliable enough. This is true but, not only is it getting better, there is a real drive from the science community for improvement, and the event organising industry is not going to ignore this. Indeed, the coming decade it would be surprising if large event facility managers, if not even the managers of larger hotels, did not install cameras into at least their large conference halls and theatres so as to feed in to an event's virtual software package.

SF conrunners could tap into this drive and some scientist SF fans participating in virtual and/or hybrid real-virtual science events might be able to provide conrunners with pointers.

In short, there are a number of possibilities and the next decade could see SF conventions change as much as they have done since the late 20th century boom in internet capability and its subsequent growth.

How much will happen is something of which I am less certain. I titled this piece 'A Worldcon Future' with an emphasis on the 'A' as there are many other options and variations thereon open to fandom. Also, Worldcon fandom is rather conservative (with a small 'c' lest some confuse this with Brit politics). For many years now (actually getting on for a couple of decades) I have been banging on about the need to split the leading (most voted on) Hugo Award categories (including novel and dramatic presentations) into two to cover SF and fantasy respectively. (However worthy, Harry Potter for the 'science fiction achievement award', really!?) Here, all that has happened is some discussion but no concrete progress. So I am not holding my breath as to what and how much of the above Worldcons will adopt. Having said that some other conventions will take these innovations onboard and think carefully about their environmental sustainability adopting only the best bits of network technology. Perhaps then eventually Worldcon organisers might begin to follow? We will see. Either way, it is likely to be interesting getting there. Increase numbers participating, being more inclusive and having greater environmental sustainability… What's not to like?

References

1. Editorial (2015) A clean, green science machine. Nature, vol. 519, p261.

2. Klöwer, M., Hopkins, D., Allen, M. & Higham, J. (2020) An analysis of ways to decarbonise conference travel after CoVID-19. Nature, vol. 583, p356-9.

3. Mallapaty, S. (2020) Conferences failing to protect LGBT+ researchers. Nature, vol. 584, p335.

4. Tulloch, A. I. T. (2020) Improving sex and gender identity equity and inclusion at conservation and ecology conferences. Nature Ecology & Evolution, vol. 4, p1,311–1,320

5. Jones, N. (2018) The information factories. Nature, vol. 561, p163-6.

6. British Petroleum PLC (2019) BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019. BPPLC: London, Great Britain.

Stop Press: Subsequent news to this article's original posting includes that SF convention organisers may want to note that scientists want a virtual dimension to events to continue after the pandemic ends.

Jonathan Cowie is a longstanding SF fan who, starting in 1979, has been on a number of convention organising committees as well as providing press liaison for an Eastercon including two combined Eastercon-Eurocons (one result of the latter was the only half-hour BBC Radio 4 programme ever made solely dedicated to a convention). In the course of his science career he has been the secretariat for numerous workshops and symposia as well as convening a couple in his own right. He is, of course, a regular con-goer and symposium participant. He can be found at science-com.concatenation.org

[Up: Article Index | Home Page: Science Fact & Fiction Concatenation | Recent Site Additions]

[Most recent Seasonal Science Fiction News]

[Convention Reviews Index | Top Science Fiction Films | Science Fiction Books]

[Science Fiction Non-Fiction & Popular Science Books]